Operational Models and Educational Debt in ATS Seminaries

Why do we care? What do we know? What can we do?

Why Do We Care?

Over the past three weeks, we have gently waded into a conversation about operational models and educational debt in Association of Theological Schools (ATS) seminaries. We began with a broad overview of our research project that looked at operational models and educational debt in ATS seminaries. Next, we talked about the three-sided challenge facing theological education. Last week, in concert with ATS, we dispelled the belief that tuition is the only factor causing rising levels of student debt.

Over the next two weeks, we will look at an infographic that shows why we care about this topic and spend a little time talking about how much debt is too much debt.

Why do we care?

We care about educational debt because it is a multifaceted issue within theological education. I care because at Sioux Falls Seminary we want to make theological education affordable, accessible, and relevant while staying faithful to the essence of the formation that should occur while a student is enrolled in seminary.

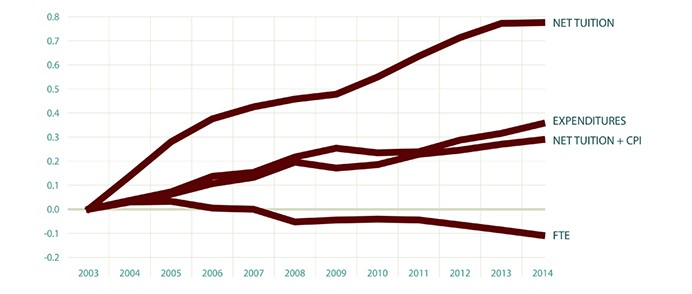

Unfortunately, our work over the past decade has, in many cases, created the exact opposite reality. Many believe theological education is exorbitantly expensive, inaccessible to most people, disconnected from local ministry contexts, and straying from the foundational core that sets our industry apart from the rest of higher education. The results are not encouraging. As the first graph in the infographic shows, despite the fact that FTE enrollment in ATS schools has declined by 11% over the past decade, the price of tuition has risen by 36% and the net tuition, or the actual funds paid by students, has risen by 78%!

Put simply, fewer and fewer students are putting more and more of their own funds into their education. It is no surprise, therefore, that educational debt levels are on the rise. At the same time, however, we know that the price of tuition is not the driving force behind increased levels of debt. Nonetheless, we believe this graph shows that we need to care about the operational and educational models we are using within theological education.

We also care about the relationship between operational models and educational debt because there may be assumptions that undergird our system of theological education that need to be affirmed or challenged. It is for this reason that our research project looked at operational and educational models inside and outside of theological education. Occasionally, we become engulfed by the belief that we have all the answers. Our natural biases can cause us to shy away from models or ideas that come from schools outside of theological education or even industries outside of higher education. To adequately address the issue of student debt, we need to embrace the reality that we may not be the keepers of pedagogical truth.

Finally, we care because we are crippling the wider church with debt. By enabling students to graduate with debt levels disproportionate to their expected income levels, we are placing a burden on the church – one that requires individuals and churches to make decisions based on money instead of mission. If you disagree with the statement that we are “enabling” students, be sure to come back and read next week’s post!

Educational debt should be an important topic for us because we, above all other educational institutions, should care about the lives we are enabling our students to live. Rather than blindly walking into a future where we become even more dependent upon debt, both as institutions and as individuals, we need to take a critical look at how and why we do what we do. We care because our students are worth caring for.