by Greg Henson, CEO Kairos University; President of Sioux Falls Seminary and David Williams, Kairos Executive Partner; President of Taylor Seminary

As the Body of Christ, it is important for us to follow Jesus in community. But who is in that community? Does it matter if we know? We suggest it does but perhaps not for the reasons many might assume. Being the “hands and feet” of Jesus means we have to actually be a body, a community. Our walk with Jesus is exactly that – our walk. Discipleship and mission are not something we should do alone. Jesus spoke the Great Commission to a community of disciples (some of whom doubted, according to Matthew 28). When we read about elders in the Bible, we always hear about them as a group. Following Jesus on mission must be done in community with others.

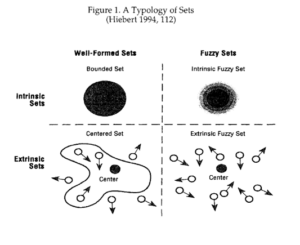

In 1978, Paul Hiebert suggested a few ways to understand who is in that community. The conversation expanded to include several pastors, missionaries, theologians, and scholars. Eventually, Hiebert created a social set model with four quadrants. Social sets are either well-formed or fuzzy and intrinsic or extrinsic. Almost no one in the conversation about social set theory uses these phrases. Instead, the three common phrases are:

- bounded sets (i.e., well-formed intrinsic sets);

- centered sets (i.e., well-formed extrinsic sets);

- fuzzy sets, which can be extrinsic or intrinsic,

The image below is from Hiebert’s book Anthropological Reflections on Missiological Issues.

There are obvious benefits to the models put forth by Hiebert. For example, four quadrants often help people understand or at least study the way different cultures tend to think about social sets.

As we noted last week, however, we think there might be a need for a new frame or lens through which to view social sets. If we are following Jesus in community, it could be that we need a new way to envision that community, a new way to know who is with us. In next week’s post, we will share some of our thinking along those lines. Our focus this week is to highlight a few reasons why our current models for social set theory within Christianity may not be quite right for the task at hand. Most of the reasons stem from a 1,500-year-old endeavor to “conquer” enemies.

The words, processes, and organizational structures one uses to share one’s theology carry significant weight in the Church. While this was certainly the case before Constantine rose to power within the Roman Empire, his need for a clear, concise, and unified articulation of the Christian faith gave theological statements enormous power. We should be grateful for the fact that his efforts helped the Church develop the Nicene Creed. Some might suggest his efforts also eventually led to the formation of Chalcedonian Christology. Nonetheless, we should also be mindful of what we lost in the process (or at least what was diminished).

The followers of Jesus, as we see them in the gospels, Acts, and the various epistles, were working out their faith in the context of community. There was a deep commitment to listening to the Holy Spirit. They were searching for “what seemed good to the Spirit.” As we noted in our first post about the Holy Spirit, the early councils of the Church continued to follow the model set by the Jerusalem council, that is they would share their findings by saying something like “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and it seems good to us that we…” According to works produced by Charles Joseph Hefele regarding a history of the Christian councils, this practice stopped with the councils that gathered under Constantine’s rule (remember, Constantine hosted the bishops and required them to attend the Council at Nicaea). According to the writings of Eusebius, Constantine opened the gathering with a speech in which he noted that, “After having, by the grace of God, conquered [his] enemies…” he had turned his attention to disagreement within the church. He went on to say, “I shall not believe my end to be attained until I have united the minds of all.” Following the decisions of the Council at Nicaea, Constantine issued a decree that if anyone didn’t agree with the decisions of the council he or she would be punished by the Roman Empire. That seems to be a far cry from “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit.” It’s more like, “I have unified the minds. Now, do what I say or else.” We would suggest that began a long history of using theological statements as the markers of what is right or wrong instead of the Fruit of the Spirit leading the way. It stunted the church’s ability to be an ongoing community of discernment.

Now, lest you forget as you are reading this, we are grateful for the Nicene Creed and for the way the Spirit worked through the Body of Christ to develop such things in spite of the cultural reasons surrounding its formation. As we noted, the Spirit works through Scripture, tradition, people, and much more do help the Body of Christ discern and do the will of God. The Spirit was obviously present in the Council at Nicaea. We are simply saying that, when compared to the previous councils, the theological statements coming out of the council were given extraordinary power because they were backed by the power of the state and enforced by the Roman army. As a result, the statements became something to fight over rather than something to discuss in the presence of the Spirit. Theology began to be more about what we say. Practicing the way of Jesus became subservient to speaking or writing the correct theology. Constantine’s edict following the Council of Nicaea didn’t say, “You will be imprisoned if you don’t behave like Jesus.” It was focused on “[uniting] the minds of all.” Toward the end of his speech, Constantine made it clear his goal was to “banish all causes of dissension.”

The coalescence of theological statements, the power of the state, and the desire to “banish all causes of dissension” began a centuries-long battle over theological boundaries – one that continues today. Herein lies the potential issue with bounded, centered, and fuzzy sets. Let’s dive into that next week.

This post originally appeared on the Kairos University blog.